Group Feedback

Overview

In this lesson, students will consider what makes the examples they and their classmates found satirical.

Preparation

- Read the lesson and student content.

- Anticipate student difficulties and identify the differentiation options you will choose for working with your students.

Ideas for a Satire

- Students can choose to do this activity with a partner or in small groups.

- Sometimes it’s helpful to talk through possibilities and to process thinking and sort the best from the worst. Questions from others prompt clarification and deepening.

- Students are nearing the end of the collecting ideas phase of this writing process.

- Students should understand that it’s not cheating to build on others’ ideas to create new ones of their own: the writing will be theirs as well as the actual thinking it evolves.

Opening

Discuss some of your ideas for your own satire. You can do this with a partner or in small groups.

- Take notes on the responses of your classmates.

- Listen to the ideas of your classmates, too, and see if that sparks any thoughts of your own.

- Add to your list of possible topics if you get more ideas!

Open Notebook

What Makes It Satirical?

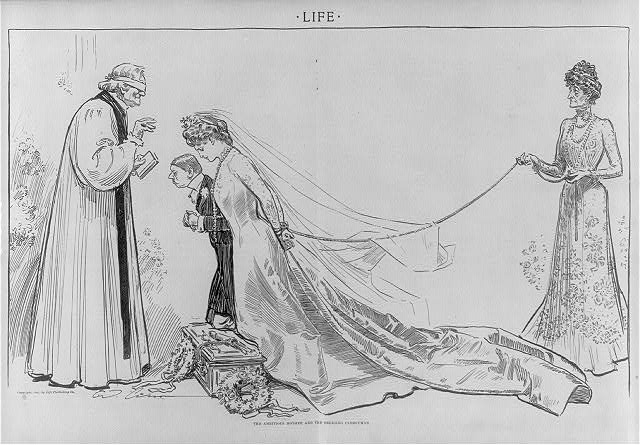

- Start with a general question that takes the class back to the unit’s central question: What is satire? How do we know it when we see it?

- You might ask for a couple of illustrations as you’re discussing the question.

- You can also tie back to Swift if you like—how was this political satire similar to or different from Gulliver’s Travels?

- ELL: When calling on students, be sure to call on ELLs and to encourage them to participate as actively as their native counterparts, even if their pace might be slower, or they might be more reluctant to volunteer due to their weaker command of the language.

Work Time

Consider the satirical examples your classmates found for homework that you viewed.

- What makes one of the examples you saw satirical?

Open Notebook

Funniest? Most Effective?

- “Funniest” and “most effective” are really quite different. Satire that’s funny without great purpose doesn’t fulfill the mission of satire, as your students will discover as they begin to discuss their choices.

- Grounding your subsequent discussion in the class’s choice will really add energy.

Work Time

Consider the following questions.

- Of the satirical examples you saw, which was the funniest?

- Of the satirical examples you saw, which was the most effective?

Be ready to explain your choices.

Satire Discussion

- You can begin with the first question by showing several of the findings—they will prompt students to remember the different satires.

- As is always true, you will want to begin with comprehension: what is being satirized in a specific cartoon, article, or clip?

- Then you can move to questions of craft: what made a satire effective or funny?

- Finally, you can arrive at the most conceptual question: which is more important—humor or effectiveness? And what’s the relationship between the two?

- Satire that isn’t funny but is effective should be present somewhere in one of the examples the students found, but if not, both Gordimer’s “Once Upon a Time” and Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” from earlier in the unit are not funny but extremely effective satires. And in fact, some would argue that satirists like Stephen Colbert are so funny that some don’t grasp he’s satirizing, undercutting his very purpose.

Work Time

Discuss these questions with your classmates.

- What aspects of American politics or culture tend to be satirized? Do you see any common threads?

- What subjects are satirized?

- Why did you choose what you did?

- What makes a specific satire funny?

- What makes another effective?

- Is it more important for satire to be funny or effective?

- Jon Stewart says that satire does not need to be funny to be effective. Is he right? Can you think of any examples?

Surprises

- Give students about 3 minutes for their Quick Write. Discuss answers if time allows.

Closing

Complete a Quick Write.

- Did anything surprise you about satires that were particularly funny and/or effective?

Open Notebook

Satirical Paragraph

- Encourage students to isolate one character trait that they possess that is ripe for satirizing. Ask them to consider the tone they adopt in writing their satires. What tone would be most effective, light and humorous or dark and biting? Remind students to share their paragraphs and to read their classmates’ paragraphs.

- SWD: Invite all students (but especially SWDs) to be creative and open and to admit to character traits that are ripe for satire.

Homework

Try satirizing yourself.

- Choose one of your own character traits that you could satirize and write a satirical paragraph. Pay careful attention to the tone you adopt for your satire of yourself.

- Share your paragraph and read the paragraphs from at least two of your classmates.

Open Notebook